[Listen]

[Sound of an ax chopping wood. Quirky music fades in…]

Christopher Gronlund:

I want to make one thing perfectly clear: this show is not about lumberjacks…

My name is Christopher Gronlund, and this is where I share my stories. Sometimes the stories contain truths, but most of the time, they’re made up. Sometimes the stories are funny—other times they’re serious. But you have my word about one thing: I will never—EVER—share a story about lumberjacks.

This time, we step back to the days of computer Bulletin Board Systems for a story based wholly on truth. (No, seriously—this was a pretty much true story, until we reach a certain point.) When two friends create an online persona to mess with another friend, they get what they have coming to them for their deception.

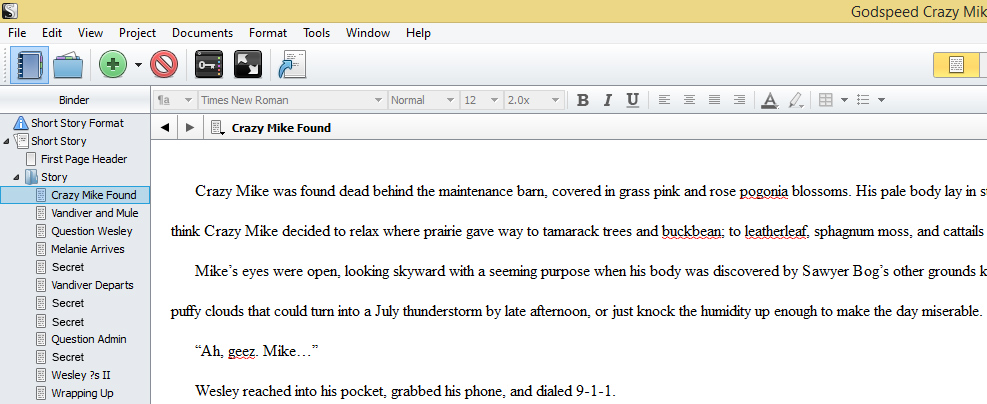

I know I said this month would be a mystery set in a bog, but that’s now been bumped to the first release of 2022. It’s a good story, and I didn’t want to rush it just to get it out. Besides, it was time for something lighthearted and goofy.

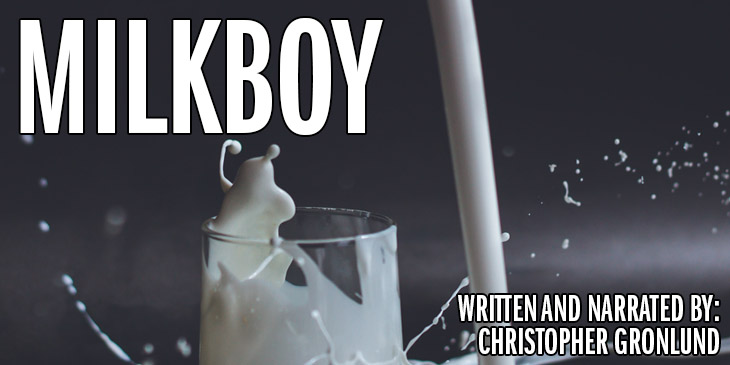

And now: the usual content advisory. Milkboy deals with emotional manipulation, stressful working conditions, infected food, passing mention of a grizzly death, demonic possession, and cartoonish violence. Oh, sooooooo much cartoonish violence! And, of course, there’s plenty of swearing.

Also, if you’re driving: be aware that anytime you hear characters in a vehicle after the mention of Yummy’s Greek Restaurant in Denton, Texas…there will be yelling, squealing tires, and even a collision. Really, from that point on…just expect the story to get louder and more ridiculous with each new paragraph.

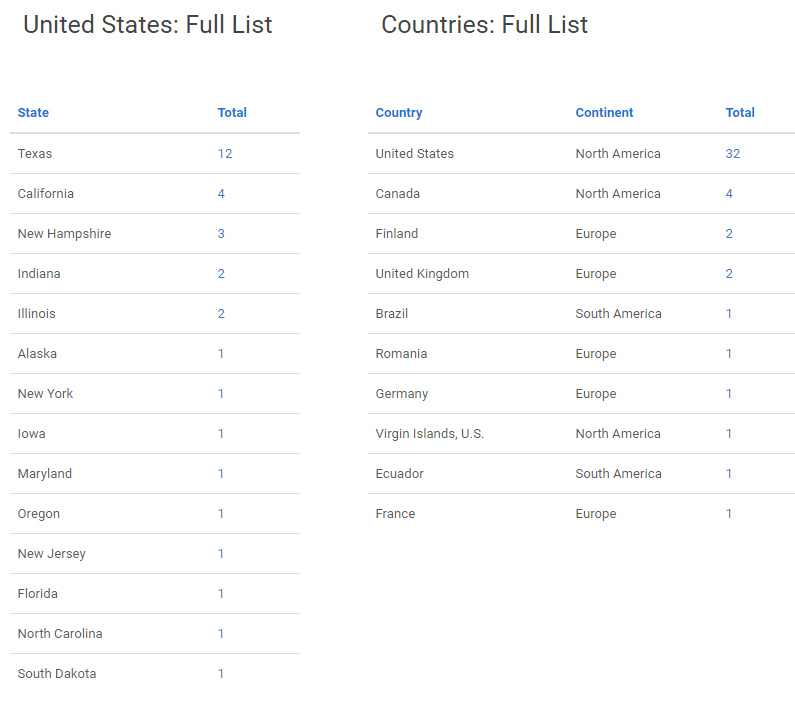

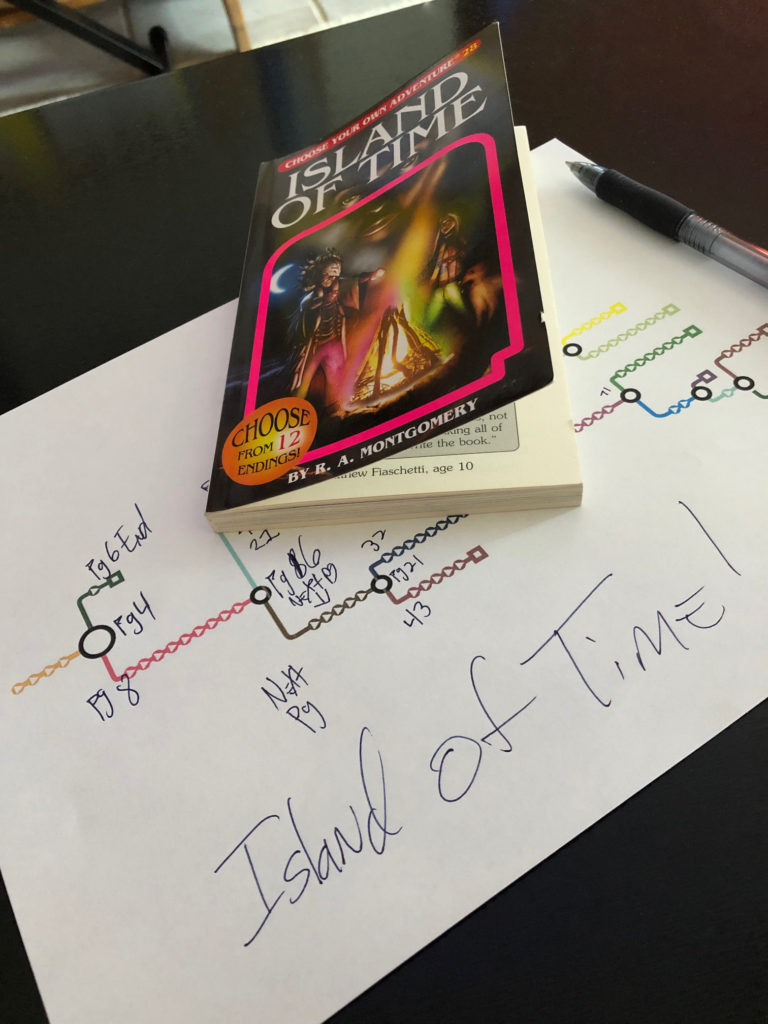

The character of Tim in Milkboy is a real person…in fact, he’s the artist behind the two versions of the Not About Lumberjacks logo! I’m releasing Milkboy today, on October second 2021, in honor of his birthday. I’ve been fortunate over the years to receive artwork from Tim as gifts on my birthday, so it was time I wrote a story as a gift for one of his. I hope this effort finally absolves me from the sin of creating Milkboy and catfishing Tim before catfishing was a thing.

All right—let’s get to work…

* * *

Milkboy

[Jaunty guitar music fades in, joined by a trumpet.]

This is a story about the shittiest thing my friend Mark and I ever did to our best friend, Tim.

Mark had a Tandy 2500 386 SX computer (with an 85 megabyte hard drive), and we put it to good use the night we created Milkboy.

Milkboy was a digital construct, catfishing before catfishing was a thing—an online persona created to see if Mark’s roommate, Tim, would take the bait.

Of course, he did.

That Tandy system, while belonging to Mark, was a shared thing in the apartment where he dwelled, a system allowing Mark, Tim, and me to log into a bulletin board system run by Mark’s manager at Two-Dice Pizza. (We chatted with strangers in the Dallas/Fort Worth area long before any of us had easier access to the World Wide Web.)

* * *

[The bleeps and bloops of a dial-up modem]

It was my idea to make Milkboy. Tim started spending more time on Jared’s BBS than hanging out with us. Looking back, I can’t blame him: he worked several jobs—among them, illustrating children’s books, delivering newspapers, and managing fireworks stands in the summer—but his most tedious task was dealing with Mark and me. Much like an exhausted parent, when the day was done, Tim wanted to connect with someone who didn’t add to his life the kinds of stresses we did.

And so, one evening he logged into the BBS and met a guy who went by “Milkboy.”

We chose the name Milkboy because Tim’s dad was not only born and raised in Wisconsin, but he was a shining Son of the Dairy State. He bowled, played accordion, and drank beer. His work ethic ran rampant in Tim’s veins—and in Milkboy, Mark and I created a fake persona that took away the stresses of Tim’s busy days. Between all his tasks, Tim chatted online with a guy who loved Wisconsin as much as he did; who loved They Might Be Giants as much as he did; who loved the exact comic books as much as Tim. It was all so obvious to Mark and me that we figured Tim would quickly realize he’d been had, but I guess when your two best friends are the kinds of people who would make up a fake person online in instead of—you know—being kinder to you…you’d believe something too good to be true when compared to your reality.

* * *

Each day, Milkboy became more perfect. If Tim talked to us about how much he loved Too Much Joy’s new album, suddenly online, Milkboy did the same. Milkboy loved Legion of Superheroes comic books, Twin Peaks on television, and could sing along to every Dead Milkmen tune. If Tim liked it, Milkboy loved it! Milkboy was a refined work in progress we enjoyed creating more than any character in the stories we wrote and the role-playing games we adored.

Not quite two weeks into our deception, Mark was the first to bring up that maybe we’d gone too far.

“It was funny when we first made Milkboy, but I’m starting to feel bad. It’s not that funny anymore. It actually feels kinda mean…”

I agreed, but…it’s a rare day when you’re part of something so new, and I wanted to see how far our online ruse could be taken. That was apparently enough of an argument for Mark to say, “Yeah, you’re right. I’m curious, too…”

* * *

And so, Milkboy’s presence grew in our lives, a thing making the three of us happy—until somewhere, almost a month in, when Tim said something Mark and I had not anticipated.

“I’m gonna see if Milkboy wants to meet up in person…”

We knew right then that we should have stopped the night Mark asked if we’d taken it too far.

Mark said, “That’s great, Tim! Cool.” Then he turned to me and said, “Hey, I’m gonna walk over to the store for some snacks—wanna come along?”

“Sure,” I said. “Need anything, Tim?”

“Nah, I’m good. I’m gonna go message Milkboy.”

* * *

Before we even made it to the parking lot, I said, “We need to go back in there and tell him the truth, Mark. I’ll tell him it was all my idea because it was, so he takes it out mostly on me.”

“He’ll kill us,” Mark said. I’m not even fully joking…he’s so stressed right now that I can see him braining us with that metal T-square he uses for art.”

[Footsteps on pavement.]

Mark was lost in thought while we climbed the hill between the apartment and the gas station store. At the top, he said, “We can have Milkboy say he’s moving back to Wisconsin. That he’d love to meet Tim, but there’s some family thing needing attention, like when you went back to Missouri when your dad died. You can play that shit up and sell it. Tim felt so bad for you. Milkboy disappears and we swear to each other, here and now, that even if we’re all still friends in thirty years that we never tell Tim the truth about Milkboy.”

“Just have Milkboy fade away?” I said.

“Yep. A message or two to Tim, and he’s gone forever.”

As long as Mark and I stuck to our new plan, it was a foolproof fix to our reckless problem.

On the way back to the apartment, Mark said, “I’ll send the first Milkboy message tonight while Tim’s delivering newspapers in Denton. We’ve got this…”

* * *

[A front door opens and closes. The sound of plastic bags.]

When we returned to the apartment with a couple bags of junk food, no sooner than we walked through the door, Tim said, “It’s done, guys. I messaged Milkboy, and he said he’d love to meet up in person.”

I don’t know what our faces looked like, but Tim said, “What’s wrong, guys? I thought you’d think this is cool.”

“No, it is,” Mark said. “Really cool. You’re sure he said he wants to meet you in person?”

“Yep. I’m gonna reply in a moment, but there was a message waiting for me. He wondered if I wanted to meet up next week at Piccolo’s Pizza. You guys, too!”

“He wants to meet all of us?” I said.

“Yeah. He sees your posts on the board and he thinks you’re cool, too.”

“Okay…” Mark said. “Yeah, sure, Tim—we’ll meet up. Sounds great…”

* * *

[The bleeps and bloops of a dial-up modem. Typing on a keyboard.]

When Tim left the apartment that night to deliver newspapers, Mark and I logged into the BBS to check on Milkboy.

We couldn’t access the account we created.

We looked at the boards and saw a few Milkboy posts we hadn’t made—mostly about music, and a post about the updated GURPS rules on the role-playing board.

In the final issue of Grant Morrison’s run on the Animal Man comic book, Animal Man meets Grant Morrison in person. Of course, it’s scripted; Morrison wrapping up his time on the series and making a heartfelt statement about childhood. A writer in control of a character. We were the writers behind Milkboy, but somehow he seemed to take on a life of his own.

“It has to be fuckin’ Tim,” I said. “He somehow found out, and he’s fucking with us in return. I bet you he strings us along a few days and then next Friday, before we all go meet Milkboy, Tim’s suddenly like, ‘Oh, Milkboy had to cancel at the last minute.’ Hell, it’s Tim…he’ll probably feel guilty by tomorrow and confess.”

* * *

Each day, Mark and I waited for him to cave in…but he never did.

And each day, new Milkboy replies on the boards popped up.

Mark decided to message Milkboy while Tim was working—not to call him out, but to see if he’d conveniently reply only when Tim got home from his paper route.

“How’s this sound?” Mark said. “Hey. Heard we’re all meeting up on Friday for pizza and beer. Looking forward to it. We can swing by your place on the way and pick you up if you want so you can drink more than just a couple beers?”

[Soft music: horns, guitar, and xylophone.]

An hour after Mark sent the message, he got a reply from Milkboy: “Oh, man…that would be so cool. Thanks! But I’m meeting up with a friend from Wisconsin after dinner with you guys. That’s the only time he could hang out…he’s in town for the weekend visiting family. You know how it is.”

Maybe the Animal Man theory wasn’t too far-fetched…

* * *

When Friday rolled around, waited for Tim to say Milkboy bailed on us, but he never did.

We sat in Piccolo’s Pizza waiting for a stranger from the BBS to arrive. Mark was likely thinking the same thing I was: Tim was going to take this to the absolute end. He’d order a bunch of food and beer—maybe even order a couple expensive drinks for himself, since I was driving—and then he’d tell us he figured out the horrible thing we did to him and stick us with the bill. We’d pay it, of course, knowing we deserved worse than that, and Tim would have something to always go back to, like Mark reminding us how horrible it was for Tim and an old girlfriend to dare me to drink Mark’s Sea Monkeys for fifteen dollars.

But Tim’s big reveal that he was onto us never happened; in fact, we watched him stand up and wave his hand to a guy wandering into the restaurant wearing a They Might Be Giants Lincoln t-shirt.

If you were given the task to make the most attractive of all geeks, you’d make Milkboy. There was a kindness to his handsome gaze; a brightness in his friendly eyes framed by designer eyeglasses. He had a Superman curl of hair on his forehead, and as I watched him make his way through the pizza joint to our table back by the kitchen, he was built like the Man of Steel as well. [Sounds of a restaurant fade in.] I could see him fronting a boy band, but give him a little scruff, and he could easily play the bad boy who made hearts swoon in movies.

“Are you Tim?” he said.

“Yes…”

He stuck out his hand. “Great to finally meet in person, Tim. I’m Milkboy, but you can call me Lance.”

After Tim shook his hand, I reached out and said, “Hey, Lance. I’m Chris.”

He almost crushed my hand as he said, “It’s Milkboy to you… Remember that.”

* * *

Mark and I may as well have stayed home. The dinner discussion consisted of Tim and Milkboy talking about all the things they loved. Tim practically shrieked with delight when Milkboy talked about how he was reading his old Kamandi comic books—and Milkboy swooned with each band Tim mentioned. Mark and I fashioned Milkboy to be a reflection of Tim, but real-life Milkboy was better than anyone we could imagine. By the end of dinner, Tim and Milkboy discovered their fathers actually went to the same high school in Wisconsin!

When the waitress brought the bill, Milkboy pulled out a wallet thick with cash and said, “It’s on me, guys.” (At least he finally acknowledged that Mark and I existed.)

From the moment Milkboy left, to the time we all went to sleep, Tim couldn’t stop talking about how wonderful dinner was.

* * *

In the weeks that followed, Tim spent more time hanging out with Milkboy than us. They were inseparable. Tuesday comic book days became Tim and Milkboy days. Tim even blew us off on Mystery Science Theater 3000 nights to go watch at Milkboy’s house.

Yeah, Milkboy had a house. A product of stout Midwest breeding, Milkboy’s father taught him the value of a dollar at a young age, when Milkboy knocked on doors offering to shovel driveways in the winter, plant flowers in the spring, mow lawns in the summer, and rake leaves in fall. Milkboy wasn’t rich, but by our terms he sure as hell was. According to Tim, he even had a Shinobi arcade cabinet in his living room.

When Milkboy came to the apartment to hang out with Tim, the only time Tim’s new best friend acknowledged us was when Tim left the room. If Tim got up to go to the bathroom, Milkboy would turn to us and say, “I don’t know why Tim hangs out with you losers. You’re a part-time pizza man and you barely work at all. He deserves much better friends.”

Upon Tim’s return, Milkboy would look at him and say, “I was just chatting with Mark and Chris about the new Tick comic book…” which would send Tim off to talk about the week’s comic shop haul.

* * *

When we finally told Tim some of the things Milkboy said to us, Tim didn’t believe it.

“I know you two are jealous about how much time I spend with him, but I still like you. It’s just…he seems to get me better than you guys…”

* * *

And so, life clicked along like that, until the following month when I got a call from Mark. I could tell by the background sounds that he was at work.

[Sounds of a busy restaurant kitchen.]

[Mark: through telephone.] “I’m sure you planned to come over tonight anyway, but you need to head over right now. I’m leaving work. I have some big news to tell you…”

[A car driving along the highway.]

On the drive over, I imagined all the things it could have been: maybe Mark had sold another indie comic book story—he sounded that excited. Maybe he finally got a tech gig instead of delivering pizzas for Jared at Two-Dice. Or maybe it was about Milkboy…maybe Tim finally announced that he was bailing on Mark and becoming roommates with his new best friend. I was not expecting what Mark told me.

“Milkboy’s a drama student at the University of North Texas. He works nights at a convenience store where Tim delivers papers. Apparently, they hit it off and chat. Tim overheard you and me talking about Milkboy. He got so mad that he wanted to fuck with us back. So, he asked his chat-buddy at the gas station if he wanted to make a little extra money acting like Milkboy.”

“How the fuck do you know all this?” I said.

“I heard Jared talking about it at work. Tim messaged him and told him we were using his BBS to mess with him. So, Jared changed Milkboy’s login, and he and Tim took over.”

“That’s shitty of them!”

Mark raised an eyebrow.

“Okay, yeah…so, we’re the shitty ones. We deserve it. But Jared?”

“He thought it was funny.”

“Well, I can’t argue with that…”

* * *

The next time Milkboy visited the apartment, we waited for the usual barrage of insults from him when Tim left the room. We were watching Northern Exposure with Tim and Milkboy when Tim announced, “Be back in a couple…gotta go get rid of some of those sausages I had for lunch…”

[Footsteps on carpet moving away.]

Before Milkboy could tear into us again, Mark cut him off.

“Stop right there, Captain Thespian. We know you’re a big ol’ pile of bullshit. A drama student? And you have the gall to rip on us for the way we live our lives?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

I said, “We know Tim paid you to pretend to be Milkboy.”

His gaze went to a beer stain on the carpet.

“When Tim comes back,” Mark said, “you’re gonna walk out that fuckin’ door and never show your face again. Understand?”

“I can do that,” Milkboy said. “Tim’s cool, but this whole thing is fucked up. And you two are assholes. Who the hell makes up a fake person to mess with their best friend?”

“It was a joke,” I said.

“Grow the fuck up, lint boy. That’s not a joke—that’s fuckin’ cruel!”

“Lint boy?”

“Yeah. You crash on everybody’s lint-covered floors and are only concerned with making enough money to buy comic books every week. You’re a little boy!”

“Hold on,” I said, “You recognized how fucked up this whole situation was, but still went along with it? Must not be making much acting money if you’re working overnights at a convenience store. You’re no better than us.”

“Am too.”

“What are you,” Mark said, “A fuckin’ fifth grader? ‘Am too…‘”

The three of us bickered back and forth until Tim returned to the living room.

“What’s going on?” he said.

Mark answered. “We know you know about Milkboy. And we know you paid this asshole to pretend to be him.”

Milboy stood up. “Tim…you’re a good guy, man. You definitely deserve better friends than these two. Later…”

[A door closes.]

* * *

When Milkboy closed the door behind him, Tim said, “What did you two say to him?”

“He was about to start insulting us,” I said. “Mark let him know we found out he was an actor.”

“How?”

“I overheard Jared at work,” Mark said. “He told me everything. When did you figure it out?”

“A few weeks in,” Tim said. “I realized Milkboy never posted when you were at work and Chris was at home. He only replied when you were all online. So, I contacted Jared. He thought my plan to turn the tables on you two was funny. Then I started chatting with Lance on my route and asked if he wanted in on it. We only planned to have him show up the night at Piccolo’s. He was gonna say that he had to go home to Wisconsin and that was gonna be that.”

“That was our plan,” Mark said. “We were gonna have Milkboy message you a couple times, saying he had to go home, and then he was gonna fade away.”

“We’re sorry,” I said.

Tim said, “You should be. Especially ’cause it’s almost my friggin’ birthday, guys! But it is kinda funny, and I can apologize to Lance next time I’m on my route. But if you ever do something like this again—I’m not fuckin’ kidding—I’ll kill you motherfuckers with my T-square.”

* * *

Things went back to normal for the three of us. We played Dungeons and Dragons, worked on comic books together, and hung out while drinking beer and watching TV. Then one evening, things got weird.

Mark and I were hanging out watching Mark’s Akira video when Tim got home from a series of school visits for his kid’s book.

[A door opens and closes.]

“Really fuckin’ funny, assholes!”

“What?” Mark said.

“Paying Lance to follow me around today. Fuck you!”

“What the fuck are you talking about, Tim?”

“Every fuckin’ school I went to, I saw Lance watching me.”

“Tim,” I said. “I swear. I mean, I know I don’t believe in God, but I swear to God…we learned our lesson and we wouldn’t do that.”

“Chris is telling the truth,” Mark said. “It wasn’t us.”

“You sure it was Lance?” I said.

Tim shot me a look. “Yes!”

“Well, maybe he’s fucking with you on his own,” Mark said. “Maybe he’s going all method actor and keeping up the role. But we have nothing to do with it this time. Seriously, Tim—it’s not us.”

* * *

It wasn’t just Tim who started seeing Lance.

Mark swore Lance was following him one night while delivering pizzas. And I never rode the Northshore Trail at Grapevine Lake faster than the day I was riding and saw Lance standing in the middle of the singletrack ahead of me. All three of us kept seeing him. [A man shouts, “Hey!” Running footfalls slap pavement.] Tim was the first to try chasing him down, but Lance turned a corner and disappeared. [Two people walking outside on a quiet night.] Mark and I saw him one night while walking to get snacks…standing just on the edge of the light cast by the gas station. We turned around to head home, but Lance was suddenly in front of us. [Two sets of running footfalls slap pavement.] Fight won over flight, and we rushed him…but he got over the hill between the apartments and gas station before us and was nowhere to be seen.

Like he’d just disappeared…

* * *

On a night Tim and Mark weren’t working, we decided to go to the source. [Interior of a car speeding down a highway.] We hopped in Tim’s Ford Escort and drove up to Denton—to the Howdy Doody convenience store at Bell and Coronado.

[Convenience store door chime.]

Lance was nowhere to be seen.

Tim approached the cashier and said, “Hey, the guy who’s usually here at night. Do you know where he is?”

“Lance?”

“Yeah.”

“You didn’t hear?”

“Hear what?”

He pointed at a newspaper. On the front page was a story about how police were still looking for the killer of a guy found murdered in his apartment a week before. The article said it looked like a bear attack. The victim’s name? Lance Fusco.

We’d all seen Milkboy earlier that day.

* * *

[Interior of a car speeding down a highway.]

“All right,” Tim said on the way home. “We’re stopping at the grocery store on the way and stocking up. Mark and I are calling in sick to work the next few days. We’re holing up in the apartment, and we’re not leaving—for anything! If, for any reason we do have to go out, we go out in a group. All three of us, understand?”

The next couple days, we were like kids during a blizzard that closed school. We played video games and Dungeons and Dragons. We watched movies and we drank beer. (Okay, so maybe it was a bit better than being kids stuck at home.) We had several days of fun, until the day Mark and I did something stupid. On Tim’s birthday, while he took a nap to stay up for a night of celebrating, Mark and I made a quick run to Denton to surprise Tim with a Middle Eastern spread from Yummy’s Greek Restaurant.

* * *

[Interior of a car speeding down a highway.]

We were speeding along the I-35 access road on our way home when it happened: a body fell from the sky right in front of us. [Squealing brakes and a loud THUD!] Mark locked the brakes, but couldn’t stop in time. It was the most horrible sound I ever heard. When we came to a stop, we looked at each other.

Mark said, “Did that look like…”

“Milkboy…?” I said.

[Doors open and close. The hissing of a radiator.]

We got out of the truck, looking at the prone body in the headlights in front of us. Neither of us wanted to be the first to approach. We waited for the other to take the first step. [Footsteps.] I took a deep breath and started toward the body. That’s when Milkboy got up.

[Gravel rustles.]

It was Milkboy, but it wasn’t Milkboy. [Breathy growl.] He looked more like the vampire from Fright Night than Milkboy—a mouth full of fangs and glowing red eyes.

[Demonic voice.] “I’ve been looking for you two…”

[Feet leap from gravel.] He moved on Mark first. [Metallic noise.] Mark reached into the bed of his pickup and grabbed the cross-wheel lug wrench. [Demonic hissing.] The cross seemed to repel Demon Milkboy. The old Baptist side of Mark kicked in. “By the Holy Gospel of Jesus Christ, stand down! You will find no safe harbor in our souls, for we are imbued with His spirit! In Christ’s name, I command ye—leave now, demon, or suffer His wrath!”

[Footsteps stop.] Demon Milkboy stopped his advance. He turned to me.

“Yeah, what he said.”

[Demon Milkboy laughs.]

[Demonic voice.] “Then I will take your friend…”

[Feet on gravel and a WHOOSH! Wings flap.]

He leaped up and flew off into the night.

* * *

[A racing engine and squealing tires.]

The tires of Mark’s Mazda B2000 pickup truck squealed as we pulled into a Chevron parking lot looking for a pay phone. [A car door closes] Mark leaped out, forgetting change. [Rummaging through coins.] I grabbed a quarter from the dashboard, [A car door opens and closes. Running on pavement] ran to the phone, [Coin inserted into a payphone] and inserted the coin. [Fingers pressing buttons on phone] Mark dialed so fast that he messed up the number. [Hanging up receiver; triggering coin return, coin returned to phone, and dialing.] He hung up, pulled the coin return, and tried again.

[Tim: through phone.] “Hello?”

“Tim, it’s Mark. You need to get out of the apartment now. I can’t explain, but Milkboy’s coming. Get the fuck out of the apartment!”

[Metal rattling through phone.]

[Demon Milkboy through phone.] “Tim can’t talk right now. He’s…occupied…”

* * *

It was easy to forget there was a time in Mark’s youth when he walked door-to-door in the hills of Tennessee, spreading the Gospel and witnessing for Jesus Christ. None of us had any reverence for faith as adults; in my case, I never did. But Mark was once a Born-Again-in-the-Blood-of-Christ-Jesus Southern Baptist, known in the hills as the boy touched by the Lord Hisself. There were aspirations to get him on A.M. radio he was so fired up on God’s Word. But his family returned to Texas, where Mark discovered comic books, Dungeons and Dragons, and goth music were far more fun than church.

[Pickup truck with engine trouble rolling down the road.]

We puttered along I-35, hoping the radiator would hold up long enough to get us back to the apartment. We were silent at first—me thinking about how I had been wrong about Jesus and demons and everything my entire life.

“Okay, I think I have it figured out,” Mark said. “That thing is some kind of quantum manifestation. Remember Animal Man 26…like that. But not just a story…totally for real.”

“It’s a fuckin’ demon, Mark.”

“No. I mean, I get what you’re getting at. It’s real, but it’s not what it seems. It’s like how some particles, when observed, react to certain laws. But it’s all chaos when we’re not looking. It’s playing by certain rules…and expects us to do the same. So, when we get to the apartment, we’re going in with the full armor of God.”

“What the fuck is that?”

“The Belt of Truth. Speak only the truth when we confront it. We’ll also be protected by the Breastplate of Righteousness—we deserved to be called out for fucking with Tim, but none of us deserve this. The Gospel of Peace will protect our feet. As stupid as we can be at times, we’re still good people not out to hurt anyone. The Shield of Faith, the Helm of Salvation, and wielding the Sword of the Spirit might be a little bit harder for you, having never believed in any of this crap. I’ll go in first and pave the way. You just think about saving Tim and putting all this behind us.

“My biggest fear is how strong it will be when we get to the apartment. It’s gonna feed off Tim’s residual Catholicism in a way no former Baptist could ever sate it.”

* * *

[Two car doors close. Footfalls on pavement.]

The apartments were silent when we pulled up. Lights were out, and no one was around. We walked to the door of Mark and Tim’s place and listened.

We heard singing…

[Demonic voice.] “Happy birthday, Best Friend. Happy birthday, Best Friend. Milkboy will never leave you. Happy birthday, Best Friend.”

Mark looked at me and said, “Remember: Full Armor of God,” as he reached for the doorknob.

[A door opens and closes.]

[Flames crackle, wind blows, souls howl.]

The inside of Mark and Tim’s apartment looked like a fire and brimstone plane of Hell. A rope bridge crossed the living room, suspended over a drop into a fiery abyss that seemed to have no bottom. In the dining room, Tim was bound to the chair at the head of the table. [Muffled cries for help.] Demon Milkboy wore a party hat and lit the candles on a [Squishing sounds] worm-riddled birthday cake with his fingertips. The rest of the table was covered with books and dice and figures from our last Dungeons and Dragons session.

[Demonic voice.] “It appears we have company, Best Friend.”

“Leave him alone!” Mark said.

[Demonic voice.] “Leave him alone? But it was you who started this…two puny humans too stupid to realize it is unwise to meddle with things you do not understand!”

“We were just fucking around.” I said.

[Demonic voice.] “There is power in words. You two, of all people, should know that. What you have manifested will now be your undoing!”

[Flames intensify.]

The demon raised its hands like something out of Fantasia’s “Night on Bald Mountain” scene, causing the flames in the abyss to rise.

“Run!” Mark shouted.

[Footfalls across a rope bridge.]

We charged across the rope bridge as the fire climbed higher. Mark’s feet and body glowed, and I swear I saw a shield pushing back flames as he scrambled across. [Snapping ropes.] The bridge gave way just as we reached the other side—[feet scratching on gravel] just enough to cause me to lose balance at the edge. [Clasping hands.] Mark extended a hand, making sure I didn’t fall in.

[Demonic voice.] “I see you wear the Armor of God,” Demon Milkboy said. “Tell me, Christopher—what do you really think about Mark?”

I imagined the Belt of Truth around my waist.

“I hated him at first. He wasn’t nice to me when I met him—he thought he was better than everyone he met. He was so fuckin’ pompous, and there wasn’t a face on the planet I wanted to punch more than his. But we each chilled the fuck out and got to know each other. There are now times I spend more time with him than Tim. I’m the writer I am largely because of Mark. More confident, too. I hope when we’re older that we still have each other’s backs.”

Mark laughed and said, “Didn’t work out the way you hoped, did it?”

“Well, what about you, False Warrior of Lies? What do you think of Chris?”

“I thought he was log-dumb when I met him. He’s still the goofiest person I know, but he’s not stupid—I was wrong to think that. And I resented him because I knew how much Tim loves him. But he’s also the reason I know Tim. We’re all sort of a fucked-up package deal, and I’ll die right here for either of them.”

“Your wish is my command!”

[Heavy footfalls running.]

Demon Milkboy rushed Mark, but I was faster. [Body tackle.] I hit him at the waist and knocked him back. [A whoosh and a thud.] One mighty swat from the demon was enough to knock me to my hands and knees.

[Demonic voice.] “The goofy one will be the first to die!”

I braced for the hit, but it never came. [Angelic energy.] A bright light filled the room. When I turned back to look, Mark held a twenty-sided die in his left hand and a silver glowing sword in his right.

[Demonic voice.] “Oh, you want to throw dice and play your little sword game? Be my guest! Your THAC0 is twenty. You cannot harm me!”

“We may throw the dice, but the Lord determines how they fall!” Mark said. [A 20-sided die tumbles across a table.] The d20 tumbled across the table and came to rest near the birthday cake.

[Demonic voice.] “Ha! You rolled a one! You are a weak little morsel.”

The light from Mark’s sword dimmed. [A heavy punch.] With one punch, Demon Milkboy knocked Mark across the dining room and into the abyss.

“Maaaaark!!!”

When the initial shock of losing Mark wore off and I remembered that I could still save Tim, I shouted, “What the fuck is wrong with you? Why the fuck are you like this? None of this makes sense! Who the fuck hurt you so bad that you go and do shit like this?”

I waited for the demon to come down on me with all its might, but it didn’t. I stood up and got face to face with Demon Milkboy.

“I asked you a question? Who hurt you?!”

[Demonic voice.] “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Yes, you do! Someone hurt you really bad to make you like this.”

[Demonic voice.]“SILENCE!!!”

“I’ll shut up if you just tell me who hurt you!”

[Demonic voice.] “Everybody! Everybody, okay?! Everybody who picked on you at Walt Whitman Junior High School. Every motherfucker who pelted Mark with biscuits in the cafeteria. Every person who made Tim feel so self-conscious about himself that he shoulders unnecessary emotional weight every day. Every person who gave Lance a wedgie before he bulked up in self-defense. I am a manifestation of all that and more—I am the pain of youth made real!“

[A sizzling droplet.]

A single tear sizzled and evaporated as it rolled down Demon Milkboy’s cheek.

“I know that shit hurts,” I said. “But it’s in the past. That was then. It doesn’t mean the memories go away and stop stinging, but you find the people who love you and don’t let go of them.”

[Demonic voice.] “That’s easy for you to say. Nobody loves me…”

[A clasping bear-hug.]

I hugged Demon Milkboy as hard as I could.

[Demonic voice.] “STOP!!! NOOOOOO!!!”

It felt like I was holding a burning tree trunk as the demon struggled to get free. [Sizzling and yelling.] I bore the pain and held tight as it smoldered and lost power. When it was done and gone, I held Lance Fusco in my arms.

“What the fuck is going on?” he said.

[Hellish sounds diminish. A call for help.]

As the hellscape faded in the apartment, we heard Mark call for help from the closing abyss.

[Running. Clasping hands; a body dragged to its feet.]

[A sealing portal.]

Lance and I rushed to the edge and pulled him up right before it was sealed beneath the carpet. We removed the gag from Tim’s mouth and untied him.

“Are you okay?” I said?

“Yeah. I think so. I have no fucking idea what just happened, but I’m fine.”

“What about you, Lance?” Mark said.

“Yeah, I’m okay. The last thing I remember was sitting in my apartment thinking about how I still have such a hard time making friends. I got pissed at myself and started pounding myself in the head. I heard a pop, like my skull opened and released something.”

“It’s a long story,” Mark said. “I dropped Tim’s birthday dinner into the abyss, but we can order pizza, drink some beer, and catch you up on the last week. You’re welcome to stay and celebrate Tim’s birthday with us. Maybe play some D&D…”

“I’d like that,” Lance said. “Happy birthday, Tim.”

“Yeah, happy birthday,” Mark and I said in unison.

“Thanks, guys. If nothing else, it’s been memorable…”

We all looked at the birthday cake on the table. The roiling mass it was before morphed into a normal cake. Mark started singing.

“Happy birthday to you…”

Lance joined in: “Happy birthday to you…”

Then me: “Happy birthday, dear Tim. Happy birthday to you…”

[A breath blowing out candles.]

[Jangly guitar music plays.]

I don’t know what Tim wished for when he blew out the candles on that cake, and I never asked him. Maybe I will someday. I don’t know if Mark or Lance made a wish, but I did—I figured, “Why the hell not? We just fought a fuckin’ demon!” And so, in that moment, I wished we’d all still be friends when we grew older and gray.

I’m happy to report it’s one of the only wishes in my life to ever come true.

[Guitar music intensifies, and then fades…]

* * *

[The sounds of full-blown Hell. Flapping wings; feet landing on rock.]

DEMON MB: Master…

SATAN: What is it, little one?

DEMON MB: Master, I am sorry I failed you, but in my stumbling, I have discovered a new way to rule His children above. A manner of temptation and addiction unlike any we could have dreamed. A mechanism of division that will impregnate their existence with chaos and compel them to destroy each other without our influence.

SATAN: Oh? Do tell…

DEMON MB: No, let me show you…

[The Bleeps and Bloops of a Dial-Up Modem.]

[Fingers typing on a keyboard.]

SATAN: [Laughter] Oh, how sinister. Oh, how utterly delicious…

[Quirky music fades in…]

Christopher Gronlund:

Thank you for listening to Not About Lumberjacks. My voice is gone—you can probably tell. Uhm…I need to work at that kinda thing a little bit better! Probably should have read all the demon voices at the end because hooooooo, I’m sure that got a little rough at the end. But…happy birthday, Tim! You suffered through so many years of friendship with us, so…my voice just suffered for you. Anyway…

I’m gonna probably do the rest of this almost in the demon voice because it comes through better.

Theme music, as always, is by Ergo Phizmiz. Story music this time is by Birdies, licensed through Epidemic Sound. To save time creating an ambient Hellscape, I licensed one of Michaël Ghelfi’s many ambient tracks. If you’re in need of background sound for role-playing games, parties, your workday, or something to fall asleep to, Michaël has your back. I’ll also be sure to leave a link to his website and YouTube channel in the show notes.

Sound effects are always made in-house or from freesound.org. I’m really losing my voice. Anyway…do I have a call at work tomorrow? If I do, they’re gonna be like, “What the hell?” and I’ll just go into the demon voice—and they’ll be like, “Wooo, something’s wrong with Chris. Why the fuck did we hire him?”

In November, the annual tradition continues as I share the most NOT Not About Lumberjacks story of the year, in honor of the show’s sixth anniversary! Yes: six years. What’s the story about, you wonder? Two deadhead loggers find something remarkable in the Piney Woods of East Texas, putting them at odds with a large timber company.

Anyway…visit nolumberjacks.com for information about the show, the voice talent, and the music.

So…until next time: be mighty, and keep your axes sharp!

* * *

[Quirky music fades in…]

Christopher Gronlund:

Thank you for listening to Not About Lumberjacks. My voice is gone—you can probably tell. Uhm…I need to work at that kinda thing a little bit better! Probably should have read all the demon voices at the end because hooooooo, I’m sure that got a little rough at the end. But…happy birthday, Tim! You suffered through so many years of friendship with us, so…my voice just suffered for you. Anyway…

I’m gonna probably do the rest of this almost in the demon voice because it comes through better.

Theme music, as always, is by Ergo Phizmiz. Story music this time is by Birdies, licensed through Epidemic Sound. To save time creating an ambient Hellscape, I licensed one of Michaël Ghelfi’s many ambient tracks. If you’re in need of background sound for role-playing games, parties, your workday, or something to fall asleep to, Michaël has your back. I’ll also be sure to leave a link to his website and YouTube channel in the show notes.

Sound effects are always made in-house or from freesound.org. I’m really losing my voice. Anyway…do I have a call at work tomorrow? If I do, they’re gonna be like, “What the hell?” and I’ll just go into the demon voice—and they’ll be like, “Woah, something’s wrong with Chris. Why the fuck did we hire him?”

Anyway…visit nolumberjacks.com for information about the show, the voice talent, and the music.

In November, the annual tradition continues as I share the most NOT Not About Lumberjacks story of the year, in honor of the show’s sixth anniversary! Yes: six years. What’s the story about, you wonder? Two deadhead loggers find something remarkable in the Piney Woods of East Texas, putting them at odds with a large timber company.

So…until next time: be mighty, and keep your axes sharp!

And now, some bloopers…

[Jaunty guitar music fades in, joined by a trumpet.]

[A wet belch.]

Christopher Gronlund:

Oh, belchy-belchy! Oh…? That smelled like a really good dinner belch. Cynthia’s been cooking lately…really good stuff. Lotta lime in that belch! Mmmm! [Sound of smacking lips.]

* * *

[Sound of distant emergency vehicles sirens.]

This fuckin’ sucks…

[Sirens intensify…Christopher mimics them.]

Now watch this be the day the apartments are actually on fire and they’re like, at the door pounding…like, “You gotta get out now! Everything’s on fire.”

And I’m like, “I’m in the middle of recording.” And they’re like, “Don’t matter, Hoss — if I gotta throw you over my shoulder and carry you down them stairs — that’s what I’m gonna do.”

And I’d be like, “I’d like to see you try. I look like a big guy, but I’ve got the weight of a fat guy, motherfucker.”

* * *

“The cross seemed to repel Demon Meek— … MeekBoy! He’s not meek—he’s fuckin’ evil…”

* * *

[Inhalation of breath, followed by a belch.]

* * *

Oh, this is shredding my voice!

[The sound of the cap on a metal water bottle being unscrewed.]

* * *

With one punch…Ugh, my voice. Getting shredded!

* * *

[Spoken line, but slightly garbbled.] With one punch…With one punch— [Mimics microphone sound.] Whoob whoob…Why is that sounding soooo bad?! [Throat clear.]

* * *

[Demon voice without deep processing]

Everybody who picked on you at Walt Whit— [Deep breath.] Everyone who picked on—Uhhhh, my voice! This is…this is terrible!

* * *

As the hellscape— Oh, my voice is gone. I-I can’t finish this, maybe… [Throat clear.]

[Music fades out.]

![A handwritten journal entry reads: 05-02-19 - Started a new job at [redacted] yesterday. And...started locking down some stuff for [redacted]. Decided it will begin w/ June in L.A. Maybe a letter from Edmund if research w/ that unit lines up. It puts June on her own...but close enough to visit Mrs. Sanders. Maybe landing the USO gig out in L.A.

But...things are moving...and that little movement feels nice.](https://nolumberjacks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/journal-may-2019-1024x768.jpg)